Thoughts on a year-and-a-half of mutual aid tech

A year-and-a-half into the pandemic and one of the few bright spots has been the growth of mutual aid societies in New York City. Initially spurred by an outpouring of volunteers and donations in mid-2020, energy has waned and taken a toll on the sustainability of these communities. As a member of Bushwick Ayuda Mutua’s (BAM) steering committee, I had some insight into this trend as we were recently forced to pause our food distribution because of a lack of resources. As a part of planning our relaunch, we were asked to reflect on what we saw as the future of mutual aid in our neighborhood, and how we could get there. The following are a somewhat haphazard collection of thoughts with a particular emphasis on the technological tools and services we (and other groups) have come to rely upon to do our work.

My first experience with mutual aid was delivering groceries weekly for Bed-Stuy Strong in the summer of 2020. I was introduced to them by my partner Amanda who had gotten involved early on in the pandemic. Over the course of a year, we witnessed as their model moved from one of volunteers shopping for families and getting reimbursed, to bulk distribution with the Brooklyn Packers, and back to the initial model, albeit with a grocery list limited to what had been available in bulk. This year we moved to Ridgewood and shifted our energies towards BAM, where we’ve done weekly deliveries and also served as the organizers of the tech team, setting up automations in Airtable, overseeing our use of Twilio for SMS-based communication, and helping to grow our volunteer base. In the past few months, I’ve joined the steering committee where I participate in shaping collective-wide strategy through a consensus-driven process. During this period, I also spent a year working at ioby.org, a small non-profit which provides fiscal sponsorship to a few of New York City’s largest mutual aid societies.

Through these experiences, I’ve come to appreciate the immense challenges facing these groups as well as their transformative potential. Here are, in no particular order, some thoughts and observations:

-

Mutual aid groups, in following the adage of “Solidarity Not Charity”, are radical not strictly for the services they offer, but in the communal structures they enact to provide them. As Michael Haber writes in Legal Issues in Mutual Aid Operations: A Preliminary Guide “the philosophers of capital have always sought to normalize extractive relationships between humans.” Creating a supportive, non-hierarchical community is therefore a radically anti-capitalist act in-and-of-itself. Doing this within the confines of an entrenched capitalist society, however, necessitates ongoing critical reflection: is providing groceries to a neighbor in need an act of charity or solidarity? The answer depends on who’s on the giving and receiving side, and whether there is potential for the roles to be reversed. When paired with the very real, very urgent needs of our community, this continual process of questioning both what we do as well as how we do it can be off-putting to some. Someone I worked with once lamented that every mutual aid meeting they attended “felt like a philosophy class.”

- This tension is also present in the tools and technologies mutual aid groups rely on to communicate, raise funds, and coordinate their work. While much has been written of the purportedly “anti-scale” approach of mutual aid groups (the lead automation engineer at Bed-stuy Strong stated they weren’t “looking for a system that scales”) the reality is that most groups relied heavily on established technological and financial platforms to quickly scale up their operations at the beginning of the pandemic.

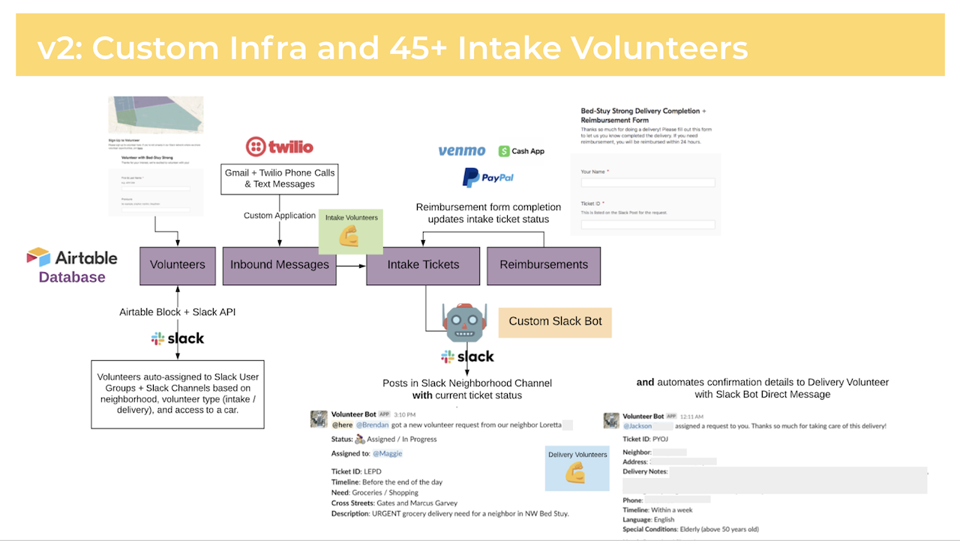

A diagram of Bed-stuy Strong's Intake System, circa May 2020. Indeed, these platforms - Venmo, Cashapp, Paypal, Airtable, Twilio, Slack, Lyft etc. - exist because they’ve applied scale thinking to their particular problem domain. While many of them have supported mutual aid work through grants, credits, and other rebate programs, I wonder how sustainable this is in the long term? If mutual aid is ultimately concerned with solidarity, then should it do so by relying on the charity of capitalist endeavors? What would it even look like to perform these services without the infrastructure that these companies singularly provide? It’s a tradeoff between responding to crises in the short term and achieving ideological coherency in the long term. Ultimately, I believe that building alternative communities of care and supporting our neighbors is too important to overly worry about which tools we’re using to do it.

-

Part of why the tools don’t matter so much is because the real work is interpersonal. Bushwick Ayuda Mutua maintains a group of defensores who maintain relationships with neighbors, facilitating food deliveries, and in-person distributions of essential goods. These volunteers do the work of building trust within the community and responding to individualized needs. It’s often difficult and emotionally taxing, especially when they have to say no to a request. Maintaining a consistent base of volunteers to do this work is challenging, and is partially why groups have been scaling down or restructuring their operations.

- The challenge of building sustainable mutual aid groups will be that of fostering a community of dedicated volunteers to do the work. While automating systems will assist in the process, these can only facilitate the interpersonal connections that make an alternative community possible. As a coordinator for the dev team at Bushwick Ayuda Mutua, it’s more important for me to foster a committed group of collaborators than it is to write code. As we start to rebuild our food program and continue supporting essential goods distributions, I hope to bring more people together to support this work.